How To Talk To Your Kid About Disabilities

Caroline Bologna | Huffington Post, March 1, 2021

Parents should discuss inclusivity and representation for disabled people with their children.

We know the value of talking to kids about inclusion, whether it’s in regard to race, gender, religion or sexuality. But what many conversations about diversity often leave out is disability.

Although the disability rights movement has made immense progress over the years, we still have a long way to go when it comes to understanding the experiences of disabled people and creating a more accessible world.

But what’s the best way to approach these conversations? Below, Dagenais-Lewis and other experts share their advice for talking to kids about disability.

Normalize disability.

“I think the most important principle that parents should have in mind is that disability needs to be normalized,” said Lydia X. Z. Brown, a disability justice advocate and director of policy, advocacy and external affairs at the Autistic Women & Nonbinary Network. “People have different ways of living and moving through the world. When deaf people are using sign language, it’s not a lesser form of communication. If someone is spinning or rocking by a fountain, it’s not weird or freakish. That’s another way of expressing joy.”

“I don’t think it needs to be a big important conversation,” said Cara Liebowitz, a writer and development coordinator at the National Council on Independent Living. “There are ways to talk about it naturally to children when and if it comes up. I think the simplest explanation is just that bodies and minds come in all different varieties, and some people are going to have more trouble walking, seeing, hearing, etc. than others. Disability isn’t really a big deal to kids ― it only becomes a big deal when adults make it a big deal.”

“One thing I say a lot when I’m talking to kids is, ‘Disability isn’t a good thing or a bad thing — it’s just a thing. It’s value neutral.’”

– KRISTINE NAPPER, AUTHOR OF “A KIDS BOOK ABOUT DISABILITIES”

Be mindful of language.

“Parents should stay clear from any euphemisms like ‘special needs’ or ‘differently abled.’ Euphemisms like that are actually deeply rooted in ableism, as it doesn’t truly address disability,” Dagenais-Lewis said.

“I always encourage parents to work through their own discomfort with the concept of disability and focus on talking about it in a way that doesn’t use a lot of cutesy descriptors and euphemisms,” Emily Ladau, a disability rights activist and author of the upcoming book “Demystifying Disability,” told HuffPost. “The more straightforward we are in our language, the easier it is to have conversations with our children.”

Many disabled people have also advocated for the use of identity-first language (i.e. “autistic person”), rather than person-first language (“person with autism”).

“We are disabled people,” said Maysoon Zayid, a comedian, actor and disability advocate. “My cerebral palsy is not my date to the prom. I can’t ditch it whenever I want to. It is part of who I am, not with me. I think that ownership helps destigmatize disability.”

Keep it value neutral.

“One thing I say a lot when I’m talking to kids is, ‘Disability isn’t a good thing or a bad thing — it’s just a thing. It’s value neutral,’” said Kristine Napper, a teacher and author of “A Kids Book About Disabilities.”

Don’t treat disability as something negative to fear, pity or feel awkward about. Statements such as “Oh that’s so sad, they don’t have an arm” or “You’re so lucky you’re not like that” are harmful. On the flip side, avoid painting disabled people as inspiring simply for having a disability.

“There’s a tendency to say something like, ‘Oh’ look at that disabled person, you should really admire them. They’re so brave. They’ve overcome so much,’” Brown said. “That may sound like a compliment, but it’s objectifying disabled people and creates the idea that disabled people only deserve respect for ‘overcoming’ their disability and that disability is so bad that it needs to be risen above.”

Emphasize treating everyone with the same respect.

“Especially for younger children, it’s important to explain that disabilities aren’t something to be afraid of and that disabled people aren’t scary — they’re people just like them,” writer and disability activist Melissa Blake said.

“I think the best thing parents can do for their children is to model the kind of behavior that they hope their child would have,” Ladau said. “If a parent cracks a joke or makes a comment, that’s the kind of thing that will stay with your children. I remember when a parent thought it was appropriate to say, ‘Watch out, she’s gonna run you over with her wheelchair!’”

Brown stressed that everyone contains multitudes, disabled or not. And disabled people are not simply charity cases or fodder for stories meant to warm the hearts of nondisabled people.

“Every person is capable of being an asshole or being a nice person. Assuming all disabled people are special, innocent angels or disgusting creatures ― both of those are dehumanizing, ” Brown said. “And if your child normally goes up to strangers to say, ‘Hello! How are you?’” they should be taught to do the same with disabled people.”

Don’t shame them for their questions.

It’s not uncommon for children to ask their parents about disabled people they see in public. They may say something like, “What’s wrong with that lady’s arm?” or “Why is that man walking funny?” This curiosity is totally natural and OK.

“It’s so important that children aren’t shamed for asking these types of questions,” Blake said. “When I’m out in public, I’ll sometimes hear children ask their parents, ‘What’s wrong with her?’ as the children point at me. So often, the parents will ignore the question or tell the children to be quiet. I just want to shout, ‘It’s OK to have them ask me!’ I seriously don’t mind answering questions like these, and I think the more honest and open dialogue that we can have about disabilities, the less those types of questions will be taboo.”

Shushing your child or telling them they’re being rude sends the message that disability is shameful and taboo. Instead of scolding, make it clear that their questions are welcome and give a straightforward answer, such as, “That person is using a wheelchair to move around.”

Say ‘I don’t know’

Children often ask why someone they observe has a disability. In this situation, it’s totally fine to say “I don’t know.”

She advised asking for permission by saying something like, “Is it OK if we ask you a question?” This acknowledges that strangers don’t owe you their personal information, and that the conversation is optional. If they don’t feel like answering, make it clear that’s perfectly OK.

“I’m almost always happy to answer kids’ questions, and I find that most other people with disabilities are, too,” Napper said. “We get this a lot, so we have our kid-friendly answers ready! And once the question is asked and answered, I also appreciate when the parent follows up with a bit of small talk about the weather or whatever. This models that disabled people are just people, and we can have normal conversations about normal things.”

Liebowitz said she’s also happy to give a simple explanation when children ask about her disability.

“I have cerebral palsy and walk with a variety of mobility aids or use a power wheelchair,” she said. “When kids ask, I usually just tell them something along the lines of, ‘My legs aren’t as strong as yours,’ and that’s enough to satisfy them. Then, I show them how my wheelchair works and the power functions, like how the seat can go up and down, and that takes away any nervousness about this weird big machine that I’m sitting in.”

If it’s not feasible to talk to the disabled person in question, parents can simply say they don’t know and explore some possible explanations, such as, “Maybe they were born with one arm, or maybe they had an accident. Lots of people have one arm or no arms for different reasons, and that’s part of who they are.”

“We can’t always see a person’s disability, but it’s still just as real. Learning about all kinds of disabilities helps us to be more mindful about recognizing and responding to needs with kindness and creativity.”

– NAPPER

Point out similarities.

Your conversations about disabled people don’t have to center 100% around differences. You can also point out similarities, whether it’s a stranger in a wheelchair who’s picking out the same brand of cereal your child likes or a friend from school who’s in the same club.

“Point out similarities ― your friend has ADHD but also loves playing Roblox like you do,” said Amanda Morin, a former teacher and associate director of thought leadership and expertise at Understood.org. “Those similarities matter to make the connection that whatever differences may be presenting are a part of who that person is but not the entire picture.”

Even if there are no clear common interests, you can speak more generally about similarities between all people.

Note that disabilities aren’t always visible.

“I think it’s also important to remember that some disabilities are visible, and some are invisible,” Napper said. “We can’t always see a person’s disability, but it’s still just as real. Learning about all kinds of disabilities helps us to be more mindful about recognizing and responding to needs with kindness and creativity.”

Morin echoed this sentiment, pointing out that understanding the reality of invisible disabilities helps kids empathize with others better.

“We can’t always see things that impact people’s everyday lives,” she said. “There are thinking and learning differences. I have significant sensory processing issues. Sometimes what seems like a behavioral response is actually a disability response, so it’s important not to jump to conclusions like, ‘That kid is acting out or being difficult,’ but instead to take a step back and ask, ‘Why might this be happening?’”

Use media.

“Read blogs, have your children read books about disabilities and differences, and watch TV shows that show inclusion,” said Ana Maritza Rivera, an American Sign Language interpreter and job developer who is part of the Diversability community. Her children’s book, “If You Could Hear My Hands,” follows a 5-year-old deaf girl named Victoria.

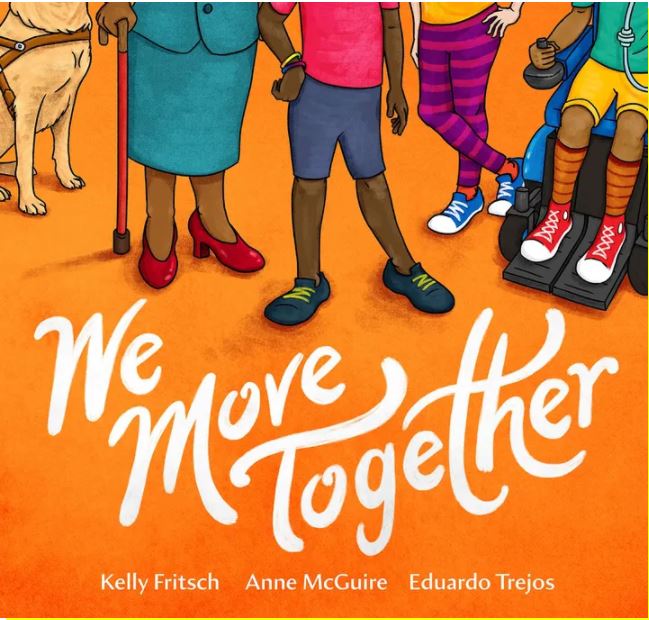

Many children’s books feature characters with disabilities, including the upcoming “We Move Together” and Napper’s “A Kids Book about Disabilities.” “Sesame Street” features the characters Julia, who has autism, and Rosita’s father, Ricardo, who uses a wheelchair. Morin suggested checking out Jessica McCabe’s YouTube channel and “Katie’s Disability Awareness Video,” in addition to resources on Understood.org. The Disability in Kidlit website also has recommendations.

“As a general guideline, I would suggest making ‘own voices’ a priority,” Napper said. “There are good books and media produced by creators who have close relationships with disabled people, but the best quality always comes from disabled people themselves.” She recommended the books “I Am Not A Label” and “Not So Different.”

Make it a continuous conversation.

“The conversation around disabilities should be ongoing,” Morin said. “You start when they’re very young, talking about how everyone has differences ― difference is just part of the human experience. For younger kids, it’s concrete thinking, humanizing the other people around them with a balance of curiosity and respectfulness. As kids get older, they can get into the understanding of what this looks like in practice.”

Parents can engage their older children in the social justice side of disability, such as learning about the history of the Americans with Disabilities Act, the disability rights movement, intersectionality and current activism in that space.

“I also think it’s important to help kids think about how we can make the world meet everyone’s needs,” Napper said. “Kids have a strong sense of what’s fair, so it makes sense to them that everyone should be welcome everywhere. There’s lots of room for good conversation about how a person’s disability might affect their needs, and how we can adapt our behavior and our world to meet those needs.”

Ultimately, the key is just to keep talking and listening.

“The biggest thing to remember is nondisabled people can be the best possible allies by engaging in open and honest conversation,” Emily Ladau said. “The sooner we do that with our children, the more easily we will start to create a ripple effect of inclusivity and acceptance.”

About This Article:

A Life Worth Living has copied the content of this article under fair use in order to preserve as a post in our resource library for preservation in accessible format. Explicit permission pending.

Link to Original Article: https://www.huffpost.com/entry/how-to-talk-to-kids-disabilities_l_60368650c5b6dfb6a735d8b4