I was born blind. Here’s how I’m using tech to access the power of facial expressions

By

When you’re blind, you can’t hear when someone smiles, much less figure out whether that smile is genuine or polite. But I’m learning.

What’s in a face, and what can a face tell you about a person? A lot, I’m told, but I have no idea. I was born blind.

I know that most faces have eyes, a nose, a mouth, a forehead, and ears, but how these parts form a whole is something I only understand conceptually. That’s because unlike sight, which takes many images and stitches them together, letting you see an entire object, touch is the opposite: It’s sequential, so you can only touch parts of an object, and then your brain has to guess what the rest of this object might be.

When I was a kid, my grandfather asked me whether I wanted to feel his face. I wasn’t sure I’d learn anything because to me, a face is just a collection of disparate parts, but I humored him anyway. He had a stubbly beard, average ears, a squat oval nose, bushy eyebrows, all the parts of a face that I’d come to expect.

“So, what did you learn?” he asked me.

“Well, I’m glad you have ears, Grandpa,” I told him.

“Oh,” he said. He sounded a little disappointed. I guess he was hoping for me to have some epiphany or that I would discover more about him. But I couldn’t, because I don’t know how these parts of the face fit together into a meaningful whole to create him.

When I went on vacation to Rome with my family in 2010, the staff at the museums let me touch all of the sculptures. There were galleries and galleries of Roman emperors’ heads. At first, touching them was exciting because I wasn’t able to access this type of sculpture in the United States. But the more heads I touched, the more they blurred together — I couldn’t read their facial expressions. Sure, one nose might be slightly more aquiline (Mom had explained the concept when I’d asked her why all the noses were so straight), earlobes on another were larger, or the eyebrows more pronounced, but that was about all I could deduce — just another collection of features, without a sense of what those features added up to. It was like touching my grandfather’s face again, but carved from cold marble.

What has always fascinated me is how effortlessly most sighted people can read faces.

There is so much information in a face that I’m not privy to. Sighted friends tell me that seeing a person’s facial expression as you talk to them adds a whole new level of complexity to a conversation — making you wonder whether their reaction is genuine, or what that split-second change in expression implies. I can hear surprise in someone’s voice, but can’t register quiet surprise, with eyebrows knitting and eyes widening silently. When you’re blind, you can’t hear when someone smiles, much less figure out whether that smile is genuine or polite.

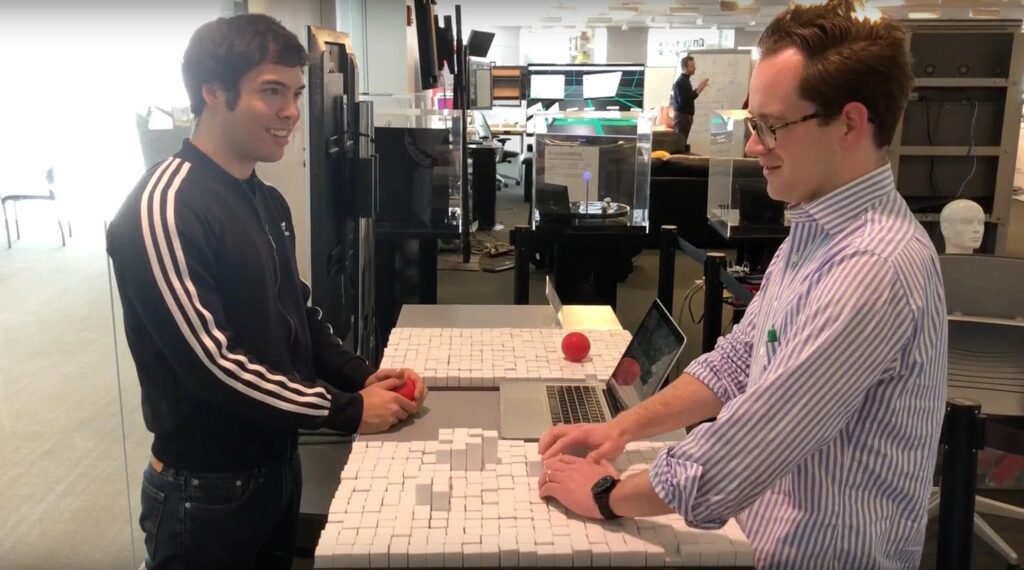

I was talking about this with some friends at the MIT Media Lab, and they called me in one day in the spring of 2018 to test out a new project they were working on. I met with Daniel Levine, then a graduate student in the lab’s Tangible Media Group — which designs “fully functioning and aesthetically pleasing tangible interfaces to bridge physical and digital worlds” — and his friend Woodbury Shortridge, a computer scientist. And, I would soon discover, they had done something incredible.

In the middle of the Tangible Media Group’s lab in Cambridge is a rectangular device called the TRANSFORM. The size of a dinner table, its surface is made up of more than a thousand square pins, each about the size of a postage stamp. These pins are connected to machinery so they can move up and down to create different shapes, reminiscent of the simpler, hand-held devices with metal pins you can press your hands against at children’s museums.

Woodbury stood in front of a Webcam, which was sending data about his facial expressions to the TRANSFORM, so the device could render a 3-D model of his face in real time.

He began to speak to me. “How’ve you been, Matthew?”

The device whirred to life, and a larger-than-life rendering of Woodbury’s face popped up under my hands. Four squares created his eyes, an upside-down T created his nose; his mouth was a massive semi-circle. As Woodbury continued speaking, I could track every movement of his facial features as they changed.

At one point, I interrupted something he was saying. “What’s in your eye?” I asked.

“Nothing,” he replied.

“Well, then why did you blink seven times during that last sentence?”

Woodbury chuckled and said, “I never realized I do that.” I don’t touch other people’s faces when I talk to them — it’s awkward for both of us, and there’s not much I can learn because facial expressions are so fleeting that you can’t feel them. TRANSFORM allows me to track facial expressions like a sighted person would, and its larger size lets me feel the nuances that I can’t feel on a real face.

As we continued talking, Woodbury’s mouth opened into an unnaturally wide oval, elongating like a boa constrictor about to eat an alligator. “What’s wrong?” I asked. “Are you OK?”

“Yep, just yawning,” Woodbury replied sheepishly.

I burst out laughing. Sure, I’d heard people yawning, and knew what it felt like myself. But being able to feel someone else yawn was fascinating.

Daniel and Woodbury had created this experience for fun, as part of their work with professor Hiroshi Ishii, director of the Tangible Media Group, but to me it was more than that. I now had access to information I’d never dreamed of, and there was so much of it that my brain didn’t really know what to do with it. Did Woodbury’s blinking mean anything, or were his eyes just dry? Now, I could match a person’s mouth movements with what they were saying. I already knew that people move their mouths when they talk, just like I do, but being able to feel it happening was a whole new experience.

I wondered what it would be like to use TRANSFORM in a real-life setting, like on a date, or during a business meeting. When I talk to people all I can rely on is what they say and their tone of voice. Any additional information that a sighted person could gather from how people dress or carry themselves is inaccessible to me.

The main way for me to learn about people is by talking to them. If, for example, I’m trying to find a friend in a crowded room, people will ask me, “What does your friend look like?” to which I say, “I don’t know, but he’s a champion beatboxer, majored in political science, speaks six languages, and sounds like Homer Simpson on helium.”

I only recently discovered that people’s eyes can move left or right without them having to turn their heads. I learned this at Disneyland of all places, outside the Enchanted Tiki Room. At the attraction’s entrance are pillars on which animatronic faces, whose eyes not only open, but swivel left and right, are mounted. I was amazed when I touched one of those faces. The process of looking at things was never something I’d thought about. In books, characters “glanced,” or “gazed,” or “stared,” but the author never bothered explaining how. They just did. For me, the fact that you could move your eyes laterally gave a phrase like “his eyes darted” a whole new dimension — they literally darted from side to side!

When I go to a place where there are people I don’t know, such as a bar, I often feel embarrassed because I assume that people are asking me questions, so I answer them, only to realize later that they were asking the person next to me. They’re facing me, so they must be talking to me, I think. I keep having to remind myself that just because their head is pointed in my direction, that doesn’t mean they’re addressing me — their eyes can swivel. If you’re sighted, how your eyes work may seem obvious, but it’s interesting to note that 80 percent of the information you receive from the world around you is visual, according to the Journal of Behavioral Optometry. Most people have access to a wealth of insight that those born blind, like me, just aren’t aware of.

Though the TRANSFORM at MIT displays the facial expressions of other people, making your own is a whole other story for a person born blind. If you’re sighted, you start learning facial expressions as a baby, smiling back at your parents. As you grow older, you see faces all around you. The flow of information is constant, with countless variations of emotions like joy, or fear, or love, and those expressions become ingrained. As a blind person, practicing and refining just one expression is no easy task.

I can call up the facial expressions that are biologically programmed into us like smiling, crying, or pouting, but adding nuance or controlling their intensity isn’t something I can do. “Smile for the camera!” my parents, who are both sighted, used to say when I was growing up in Newton. I’d try and give them a genuine smile. “Why are you scowling?” they’d ask. “I thought that was a wide smile,” I’d explain.

I’m an opera singer, studying at New England Conservatory, and perform on stage a lot. When I’m practicing, I’m always afraid that I’m under- or overdoing an expression, but walking the line between smile and scowl is hard when you can’t see. Trying to get a genuine smile out of me for a picture is like being a wildlife photographer — you never know when it might happen. I also always have to be ready, trying to figure out what caused such a genuine expression, and what muscles I used to create it, so I can hopefully re-create that real smile in the future. Because polite smiles are usually held longer, they take more energy and muscular control than genuine ones; after five seconds of smiling politely, my muscles start twitching — they’re not used to working so hard. I don’t know how people in the service industry can keep smiles on their faces all day — my face would fall off.

As a sighted person, you can stand in front of a mirror and test out your facial expressions. Sighted actors practice like this all the time. I, however, have to rely on feedback from parents or friends for guidance. Most of the time, my expressions come across as too manufactured, too put on, so my parents tell me to just not use them at all.

To learn the nuances of my own face, I’m creating a device that uses vibrating motors to train my facial muscles. I’d seen similar technology used to help stroke patients regain control of their faces, so thought it could be used to help me and other blind people be more expressive.

The FaceFlexer is a mask that the user wears, with motors positioned at the 42 facial muscles that we use to create facial expressions. Images of different facial expressions can be loaded into the FaceFlexer, which converts them into short vibrations to work out your facial muscles. For example, if you were practicing a look of disgust, and wanted to learn how to wrinkle your nose, something I can’t yet do on command, you could import that expression into the FaceFlexer, and it would vibrate your nose into compliance.

I can’t knit my eyebrows, either — I’ve simply never used the muscle responsible for bringing them together into a look of concern. Hopefully, the FaceFlexer could build that muscle for me, too. It’s a wacky device, but I crave the control that sighted people have over their faces. That level of facial nuance would open up a whole new realm of expression for me and would be invaluable to me as an actor. Because actors who are blind since birth lack the facial expressivity that casting directors expect their characters to have, be they blind or sighted, casting directors usually cast sighted actors to play blind characters. Blind actors are rarely cast.

I’m never sure how I’m perceived by my audience when I perform. When I did a TED Talk about a system of text-based instructions my friend and I created that lets blind kids build LEGO sets on their own, I couldn’t see my audience or read their body language. To assure myself that they weren’t falling asleep, I inserted humor at various moments. If they laughed at the right times, then I knew that they were awake and engaged. Because I can’t see my audience, I perform as energetically as I can. If I’m giving them my all, then at least I know that they’re focused; it’s hard to drift off when you’re being enthusiastically told about how building LEGO sets helps blind people learn about the world around them, or what it’s like to narrate a movie for blind viewers.

At the MIT Media Lab, Woodbury and Daniel are planning to work on creating a miniature version of the TRANSFORM, about the size of an iPad, so I can test it in the wild. Until then, I’ll still be in awe at the power of a face, and all that it can convey.

Matthew Shifrin lives in Newton and hosts the Blind Guy Travels podcast on PRX’s Radiotopia. Send comments to magazine@globe.com.

About This Article:

A Life Worth Living has copied the content of this article under fair use in order to preserve as a post in our resource library for preservation in accessible format. Explicit permission pending.

Link to Original Article: https://www-bostonglobe-com.cdn.ampproject.org/c/s/www.bostonglobe.com/2021/08/25/magazine/i-was-born-blind-heres-how-im-using-tech-access-power-facial-expressions/?outputType=amp