Deaf researchers are advancing the field of science — but barriers still hold many back

CBC Radio | December 4, 2021

As attitudes slowly change, Deaf researchers are bringing their unique perspective to the lab and the field

In a scrubby patch of forest near Halifax, Saint Mary’s University professor Linda Campbell and her master’s student, Michael Smith, squelch through mud, looking for lichens. The lichens they’re after can be used as natural biological monitors of pollutants from former gold-mining sites, like this one.

Smith lifts one piece from a branch. It’s usnea, or beard lichen, which the researchers can use to assess levels of arsenic and mercury in the air. That’s because it absorbs nutrients — and pollutants, if they’re present — from the atmosphere rather than through roots.

Campbell notes that there were once industrial devices used to crush gold-bearing ore at the site where this lichen is now growing. The lichen is absorbing mercury initially released from the ore many years ago, that is still percolating out into the environment. “What took place 100 years ago is still being reflected in the lichen,” she said.

Campbell is a freshwater ecologist — one of a handful of experts in Canada who’s studied how contaminants move through ecosystems, and how to deal with them.

But she’s also part of another minority. Campbell is Deaf, and uses American Sign Language, or ASL, making her part of a group that continues to be underrepresented in science.

A report from earlier this year by the Royal Society in the U.K., for instance, noted that while about one per cent of the population is deaf, the percentage of STEM undergraduates in that country who are deaf has stagnated at just 0.3 per cent for the past decade. And, a 2017 U.S. study by the National Deaf Center on Postsecondary Outcomes found that, overall, Deaf people obtain lower levels of education than their hearing peers.

In Canada, there is little formal data, but, anecdotally, Campbell knows of only five other deaf STEM university faculty members.

Campbell attributes the underrepresentation to barriers erected by attitudes among hearing people.

“When science looks at that as an added cost, and added labour, to include people with disabilities, they’re not recognizing the differences and the successes that can be brought — that diverse thinking can be successful.”

Barriers rooted in education

Alex Lu recently graduated with a PhD in computer science from the University of Toronto, where he studied Artificial Intelligence, or AI. Lu is Deaf, and uses sign language and lip reading, as well as his own voice.

Growing up, Lu says he always felt comfortable as a Deaf person, but found that hard to reconcile with the attitudes he encountered in his university education. He found people were used to teaching and learning science a certain way — which didn’t always involve working with Deaf people or ASL interpreters.

“I think I’m the first Deaf person in my program. So there was a whole bunch of confusion about how you get ASL interpreters and how they work in classes. There were a lot of professors that had never interacted with an ASL interpreter, or a student that uses an ASL interpreter,” he said.

“And then when you start looking into that, you start realizing, well, here are all of the barriers in the way that we’ve been educating deaf people.”

Some of those barriers can be traced back to the fact that, from the late 19th century to the early 1960s, sign language was often forbidden in education, as people believed it prevented Deaf children from learning speech.

ASL often not built for science

Today, there are few Deaf researchers working in academia, which has led to a problem: much of the technical and specialized language used in STEM hasn’t made its way into signed languages such as ASL.

When there are no signs, interpreters may use fingerspelling — spelling out each letter of a word — or the sign for the word in general English, which can be inaccurate.

Colin Lualdi, a fourth year PhD student at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, studies photonic quantum information. He said the lack of useful signs can be frustrating and tedious for deaf students, and can produce misunderstandings.

One example was the term “degeneracy,” which he encountered as an undergrad. His ASL interpreter signed using the English word meaning to get worse over time. In fact, in physics this actually refers to two systems with the same amount of energy.

WATCH | Physicist Colin Lualdi defines the physics concept of ‘spin’ in ASL:

“And by that time, I realized we needed a new sign for it, in order to support the concepts that were being communicated,” he said.

Since then, Lualdi has joined a collaboration between Harvard University and the Learning Center for the Deaf to create signs for terms in quantum science. One of the signs the team has worked on is for electron; the current sign has an index finger circling a closed fist, representing a nucleus.

“It implies that you have an electron always circling a nucleus, right? But that’s not always true,” he said.

Instead, Lualdi and other project members have proposed a sign with just the index finger moving in a circle.

WATCH | Physicist David Spiecker demonstrates the proposed new ASL sign for the electron:

They’re now in the process of disseminating this sign and others, as well as syntax the project has been working on to improve communication of physics concepts, to see if they’ll be adopted by the broader community.

Either way, Lualdi says they’ve already made his own work as a scientist easier.

“Everyone wins when we have an improved framework of language and, and the process becomes much more efficient.”

Bringing a unique perspective to fieldwork

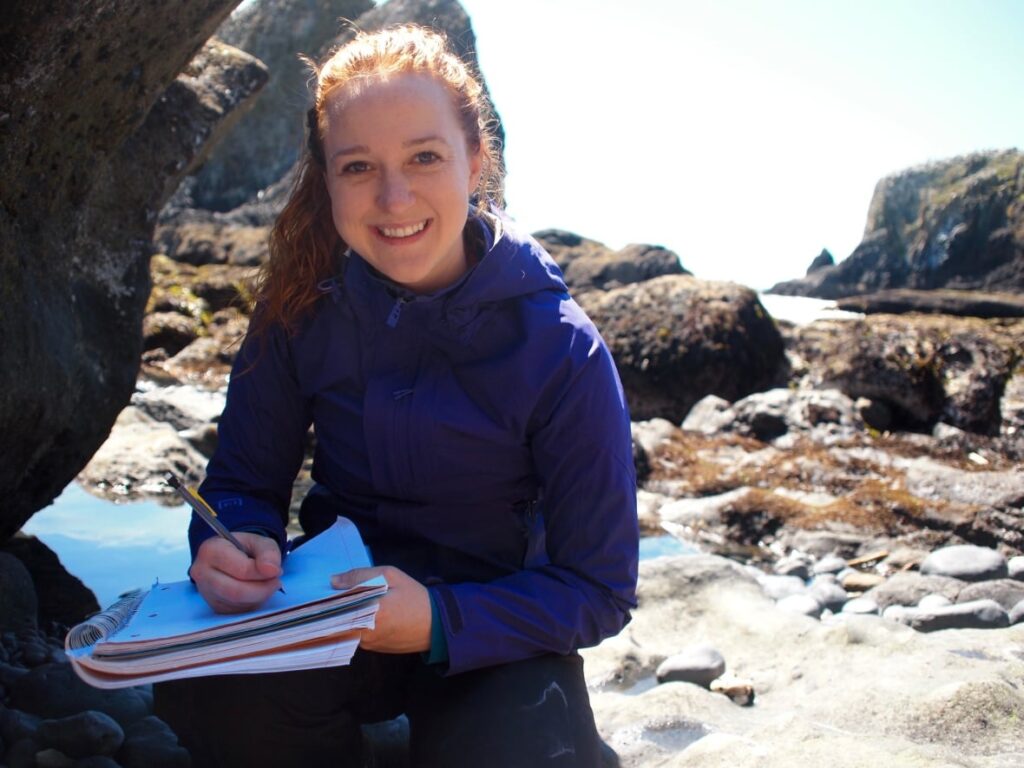

Outside of physics labs, being Deaf in science can present its own challenges and opportunities, as it did for Barbara Spiecker. She came to love fieldwork while pursuing her masters degree in marine biology.

Spiecker, who is now doing a post-doctoral fellowship at the University of California, Santa Barbara, said her experience as a Deaf scientist, and a user of ASL, have honed her powers of observation, and provided her with a different lens to view the natural world.

“It’s very 3D based, a lot of what I do, and ASL is a 3D language. So often hearing people, when they research, have a different frame of how they see and interpret the world, and what they research. So, that’s what I bring to the table,” Spiecker said.

But Spiecker says being Deaf hasn’t always been seen as a strength. For the first two years of her PhD program, she was not provided an interpreter, which meant she missed out on learning opportunities. Spiecker says she had to fight hard to not have the cost of the interpreter pushed on her lab, which would have cut into their research budget and discouraged them from hiring Deaf students.

“That was quite the battle — if that was allowed, then I wouldn’t have got my PhD.”

In fieldwork, too, she encountered attitudes that could present obstacles. At one point, her work involved extended time on the seaweed carpet of the potentially treacherous intertidal zone. Advisors and potential employers expressed doubt she could be safe in the water.

“I [was] like, ‘there’s really no difference, you probably aren’t relying on your hearing at that point, either.’ My eyes are very vigilant in these situations,” she said.”It just took a little education and explanation, to help them realize there’s really no difference.”

The value of different perspectives

But Alex Lu says there is a difference in once important way — in that Deaf scientists, by virtue of their life experiences, contribute different perspectives.

“The value of having disabled people in science, and marginalized people in science isn’t that you just want to get people who are uniformly going to be superheroes or anything like that,” he says. Instead, he says what’s important is that “we contribute perspectives that are different from mainstream science.”

Back at the former gold mining site, Linda Campbell says science is strengthened by having more people contributing diverse perspectives, such as the issues she works on, challenging legacy contaminants affecting ecosystems.

“We’re building many lines of evidence for the research and the potential risks of the tailings and how to manage those risks,” she said. When barriers prevent Deaf scientists from contributing to these kinds of challenges, she said, “you’re losing that whole group of people who have such intense, powerful skills that can advance the field of science.”

And the fact that some Deaf scientists have managed to work and advocate their way into positions working on environmental issues and other aspects of STEM doesn’t mean that the barriers have been removed — instead, she said it should be seen as inspiration for work that is still to come.

“There are many, many more people that could be successful and could contribute to science and make the planet a more healthy place. But they just can’t, because of those very barriers imposed on them,” she said.

“‘If they can do it, you can do it’ — that’s not it. It’s more that ‘they could do it, so we can find a way for you to do it, too.'”

About This Article:

A Life Worth Living has copied the content of this article under fair use in order to preserve as a post in our resource library for preservation in accessible format. Explicit permission pending.

Link to Original Article: https://www.cbc.ca/radio/quirks/dec-4-xenobot-self-replication-red-light-for-declining-vision-water-from-the-solar-wind-and-more-1.6269551/deaf-researchers-are-advancing-the-field-of-science-but-barriers-still-hold-many-back-1.6269553