Curb Cuts

By 99pi | April 27, 2021

if you live in an American city and you don’t personally use a wheelchair, it’s easy to overlook the small ramp at most intersections, between the sidewalk and the street. Today, these curb cuts are everywhere, but fifty years ago — when an activist named Ed Roberts was young — most urban corners featured a sharp drop-off, making it difficult for him and other wheelchair users to get between blocks without assistance.

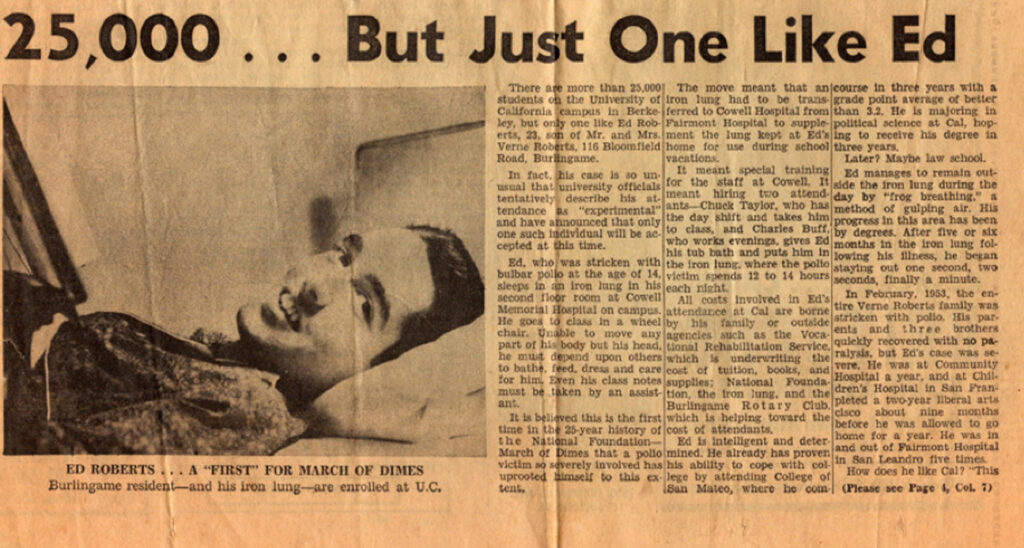

Roberts was central to a movement that demanded society see disabled people in a new way. He’d grown up in Burlingame, near San Francisco, the oldest of four boys. He was athletic and loved to play baseball. But then, one day when he was 14 years old, he got really sick.

He had polio, which damaged his respiratory muscles so much that he needed an iron lung to stay alive. The polio left Roberts paralyzed below the neck, only able to move two fingers on his left hand.

In order to escape his iron lung once in a while, Roberts taught himself a technique called “frog breathing,” a deep-sea divers’ trick of gulping oxygen into the lungs, the way a frog does. For polio survivors, whose weakened breathing muscles weren’t strong enough to inhale that needed oxygen, “frog breathing” meant a person could get out of the iron lung for short stretches of time. Roberts was told it was bad for his health, but he kept doing it, determined to live on his own terms.

Roberts was tenacious, but everything was hard. He needed the iron lung while he was asleep, but during the day he stayed in school, going to campus once a week. When Ed left the house, his family would run the maneuvers, helping him navigate a world that wasn’t built for a person in a wheelchair. They’d lift him over curbs, and up and down stairs. When his mother, Zona Roberts, went out with him alone, she would enlist strangers to assist.

Roberts graduated from high school, then from a local community college, but in 1962, when he wanted to go on to U.C. Berkeley, the university initially turned him down. Among other things, administrators weren’t sure where he could safely live — his iron lung wouldn’t fit into a dorm room. Eventually, someone suggested housing Roberts in the campus hospital, inside a patient room remade into a living space.

On campus, an attendant would wheel Roberts to each class, where he would recruit a classmate to help him take notes — they would use a piece of carbon paper to create a copy for him. “It’s such a simple way to take notes,” Roberts recalled, “and of course to meet people and get them involved with you. So there were all these little gimmicks.” Roberts did so much studying and reading that the mouth wand he used to turn the pages of books started to push his teeth out of shape

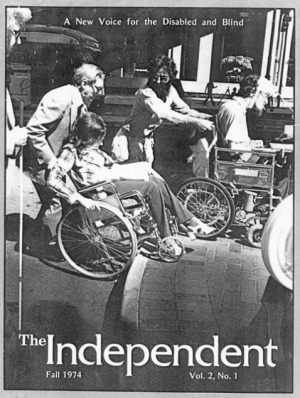

His story began to make newspaper headlines. Soon, a second quadriplegic student moved into Roberts’ makeshift hospital dorm— a young man who’d been paralyzed in a diving accident and was initially told he should just get used to life as a shut-in. Then a few more arrived, both to live in the hospital and to find lodgings off campus. The word started to spread: something unusual was going on at Berkeley.

These students had profound and visible disabilities. The state paid special attendants to heft their wheelchairs up staircases and into lecture halls. It was hard to miss the new presence on campus.

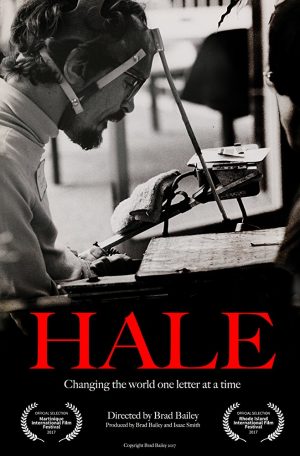

And all of this was happening during the 1960s, “a time of lots of protests, and lots of reform, and lots of change,” explains Steve Brown, co-founder of the Institute on Disability Culture. On the Berkeley campus, the hospital housing students also became the headquarters for an exuberant and irreverent group of organizers. This group called themselves the Rolling Quads and it included Roberts as well as Hale Zukas, an assertive guy with cerebral palsy who communicated with a word board and a pointer strapped to his head.

Like other coalitions of disabled young people around the country, the Rolling Quads started using a new kind of language to talk about their needs and rights. They were advocating for what was then a radical idea: that people with disabilities had civil rights, too. The right to education, to jobs, to respect, to real inclusion in public life. This all fit right into the revolutionary spirit of the 1960s and early 70s.

One member of the Rolling Quads, Deborah Kaplan, explains the widespread cultural stereotypes the group was trying to take apart: “That having a disability is a fate worse than death. That we should be pitied. That if we do anything we are brave, and yet [we’re] really not real people.” These kinds of views were reinforced by events like the annual Jerry Lewis Telethon. The telethon was the late comedian’s annual marathon fundraiser for muscular dystrophy. He mugged for the camera, and brought in celebrity singers, and spent a lot of time smiling down at cute, well-dressed children in wheelchairs. The rising generation of disability rights activists hated it.

“We would just cringe every Memorial Day weekend, knowing that all these people were watching Jerry Lewis squeezing money out of people by dramatically playing up the most horrid stereotypes about disability that we had to combat,” Kaplan explains.

Back at Berkeley, the Rolling Quads — and Ed Roberts in particular — were one big antidote to the Jerry Lewis telethon. Roberts flirted with women, got arrested in college for peeing outside a bar, and told dark jokes about quadriplegia. A testing counselor once pronounced Roberts to be “very aggressive” — he liked recounting his response: “Well, if you were paralyzed from the neck down, don’t you think aggressiveness would be an asset?”

“The nature of access, of being included, meant that you had to in some ways force yourself upon the world,” says Lawrence Carter-Long, of the Disability Rights Education and Defense Fund.

“Because the tendency, the programming, for the rest of the country — even here in Berkeley at first — was to say, ‘We don’t want to see that. You’re going to make those normal people uncomfortable!’”

But by the time Ed Roberts was in graduate school at Berkeley, the disabled students were noticeably and unmistakably part of the community. Even more so because some were zipping around in power chairs, which had been invented to help wounded veterans and were starting to be more available to the general public.

Roberts got interested in power chairs when he first watched another quadriplegic try one out. And he now had a new portable ventilator that attached to his wheelchair. So even though he still used the iron lung at night, he could stay away from it a lot longer. And… there was a girl. Which, he remembers, made it “ridiculously inconvenient for me to have my attendant pushing me around in my wheelchair with my girlfriend. It was an extra person that I didn’t need to be more intimate.”

But think about this. For more than a decade you’ve been able to get around because somebody’s behind you pushing your chair, and now you’re under your own power. You get to leave that wheelchair attendant behind, but still, you have to contend with… curbs.

“If you’re trying to get across the street and there are no curb cuts, six inches might as well be Mount Everest,” says Lawrence Carter Long. “Six inches makes all the difference in the world if you can’t get over that curb.”

The power chair riders — actually all the wheelchair riders — needed what we now call “curb cuts” — those slopes at the corners that make it easy to roll between sidewalk and street.

The Early History of Curb Cuts

Back in the 1940s and 50s, there were a few communities across the country where people had tried to make elements of the built environment more accessible. For example, there was a coach in Illinois working with disabled soldiers who badgered reluctant officials at the University of Illinois — until finally, the school set up a rehab and education program with wheelchair sports and wood ramps into buildings.

Historian Steve Brown discovered another example in Kalamazoo, Michigan. Kalamazoo had extra high curbs. After WWII, a retired veteran got so fed up watching other disabled vets struggling to cross the street that he persuaded city officials to cut ramps into the sidewalks at four downtown corners.

But by the late 1960s and 70s, the new wave of young disabled activists wasn’t going to wait around for the occasional enlightened college coach. They demanded. They were insistent. They didn’t wait for permission.

To this day, stories circulate about the Rolling Quads riding out at night with attendants and using sledgehammers to bust up curbs and build their own ramps, forcing the city into action. But Eric Dibner, who was an attendant for disabled students at Berkeley in the 1970s, says “the story that there were midnight commandos is a little bit exaggerated, I think. We got a bag or two of concrete,” he elaborates, “and mixed it up and took it to the corners that would most ease the route.” While it did happen at night, they only hacked a few curbs.

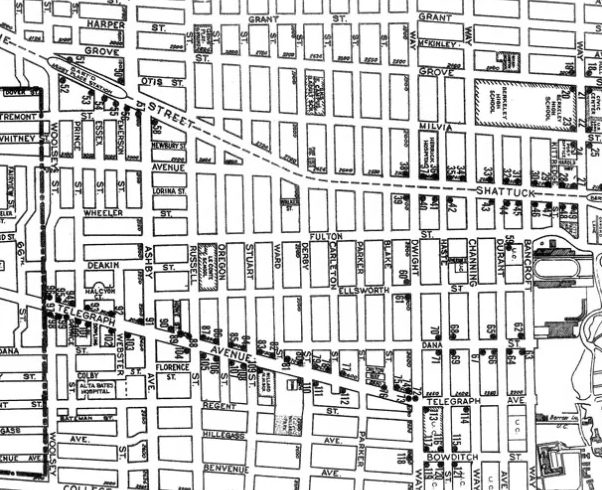

In reality, most of the progress made by the Rolling Quads was a little more bureaucratic. One day in 1971, the group showed up at the Berkeley City Council. Ed Roberts, by then a political science graduate student, was there. And so was Hale Zukas, who was learning Russian and finishing a math degree. So were a lot of their friends, both disabled and not. Together, they insisted the city build curb cuts on every street corner in Berkeley. And their call to action sparked the world’s first widespread curb cuts program. From the city council minutes on September 28, 1971: “Declaring it to be the policy of the city that streets and sidewalks be designed and constructed to facilitate circulation by handicapped persons within major commercial areas … That curb cuts be made immediately at fifteen specified corners …. The motion carried unanimously.”

Beyond Berkeley

By the mid-1970s, the disability rights movement was growing and spreading, with groups around the world advocating for changes in the built environment to enable more independence. This didn’t just mean curb cuts, but also wheelchair lifts on buses, ramps alongside staircases, elevators with reachable buttons in public buildings, accessible bathrooms, and service counters low enough to let a person in a wheelchair be attended to face-to-face, and more.

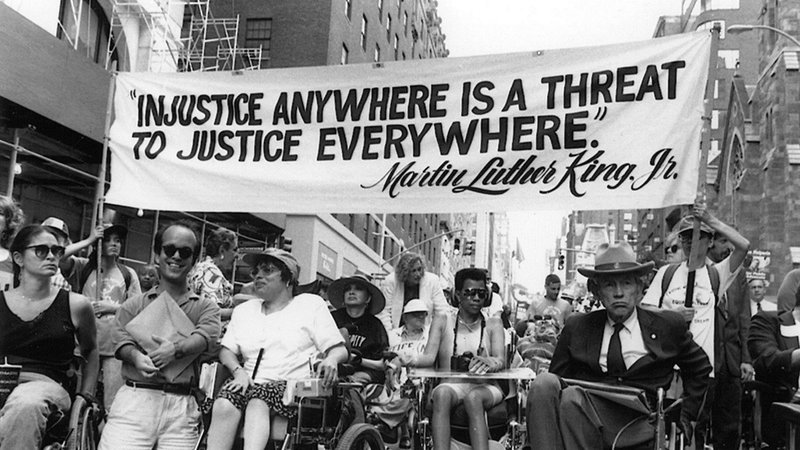

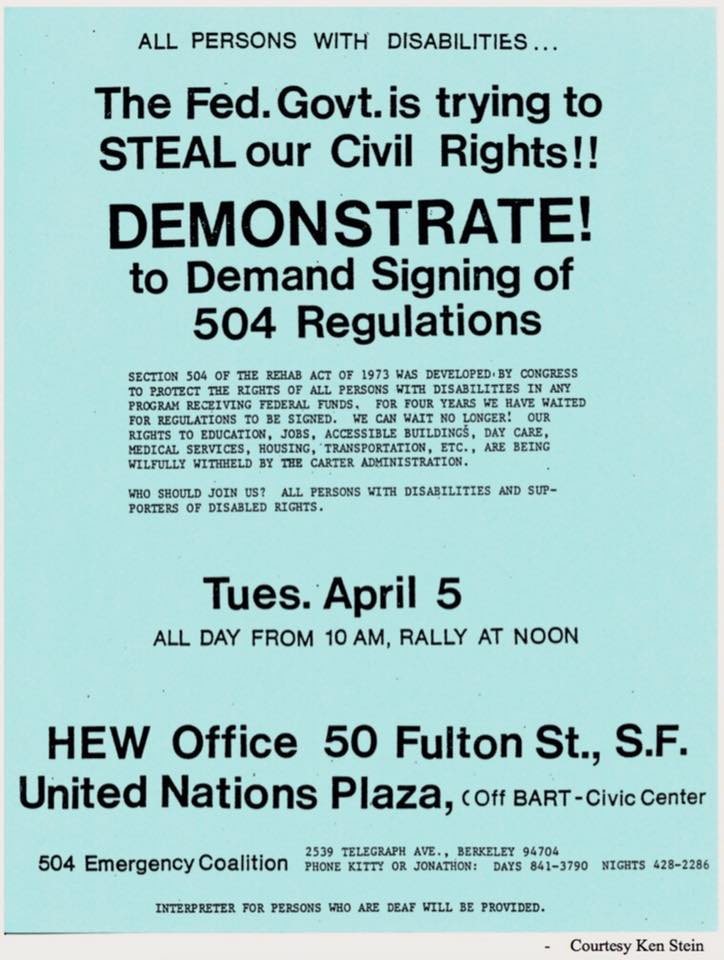

In 1977, disability rights protesters hit federal office buildings in eleven cities at once. They were pushing the government to act on long-neglected rules protecting the disabled in all facilities taking federal money. The protest in San Francisco turned into a month-long sit-in, with steady news coverage of people in wheelchairs, taking care of each other and refusing to leave until action was taken.

In 1980, disabled people in Denver staged a protest demanding curb cuts. They’d already blocked traffic until city transit officials promised to put wheelchair lifts on all the buses. Demonstrators in wheelchairs leaned over, for the photographers, to whack at concrete curbs with sledgehammers.

And in 1990, when the sweeping Americans with Disabilities Act was hung up in the House of Representatives, disabled demonstrators left their wheelchairs and crawled up the marble steps of the Capitol building to make sure the bill went through.

The ADA wasn’t the first federal legislation designed to remove barriers for disabled people, but its reach was unprecedented. It mandated access and accommodation for the disabled in all places open to the public — businesses, lodgings, transportation, employment. It had qualifiers, to be sure — the ADA required only what was “reasonable,” for employers and builders and so on. There was a lot of argument about that word. But at the bill’s signing ceremony in 1990, President George H. W. Bush spoke with emotion about the recent fall of the Berlin Wall, which had divided communist East Germany from the West:

“And now I sign legislation, which takes a sledgehammer to another wall, one which has for too many generations separated Americans with disabilities from the freedom they could glimpse but not grasp. And once again we rejoice as this barrier falls, proclaiming together, we will not accept … excuse [or] tolerate, discrimination in America.”

The Legacy of Ed Roberts

Ed Roberts, who U.C. Berkeley officials once thought was too crippled for their university, finished his master’s degree, taught on campus, and co-founded the Center for Independent Living, a disability service organization that became a model for hundreds of others around the world. He also married, fathered a son, divorced, won a MacArthur genius grant, and for nearly a decade ran the whole California state Department of Rehabilitation Services. He was 56, an international name in independence for the disabled, when a heart attack killed him.

A special memorial was scheduled for him at the annual march and meeting of the National Council on Independent Living in Washington, D.C. Marchers followed Roberts’ empty wheelchair which was being dragged along by his attendant, until they reached the Senate office building. Once inside, speakers got up to honor Roberts’ life and legacy. Senator Tom Harkin from Iowa gave a eulogy, noting that when Martin Luther King Jr. died, they built statues to honor him. But Harkin said there was an even better way to honor Ed Roberts, a warrior for another kind of civil rights. Barriers would be torn down in his name. Every curb cut would become a memorial for Roberts.

Today, Roberts’ wheelchair is stored at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History, and remains on permanent display on their website. But the struggle continues — curb cuts are common now, but they’re not at every intersection, even in Berkeley. And a lot of assumptions persist about what people with disabilities can do, achieve, and enjoy.

“We’ve not yet accomplished full inclusion,” says Lawrence Carter-Long. “We have managed to make it easier, by and large, for people to get into the building. But have we done the work that’s going to make it easier for them to get the education? For them not only to have a job, but have a career? Those things still don’t exist for many people, even in Berkeley.” The work remains.

About This Article:

A Life Worth Living has copied the content of this article under fair use in order to preserve as a post in our resource library for preservation in accessible format. Explicit permission pending.

Link to Original Article: https://99percentinvisible.org/episode/curb-cuts/

Podcast Transcript:

Roman Mars:

Hello, Beautiful Nerds. I have a big announcement. After 10 years of being an independent production with our 10th year probably being our biggest ever – putting out three special projects, spinoffs, and a best-selling book – I have decided to sell the show to SiriusXM, specifically to Stitcher, which is their podcast company. The same 99pi crew are going to make the show. I’m still going to host it. We’re our own editorial unit. It’ll still be available anywhere to everyone. If you’re subscribed now, you will stay subscribed. It’s the same show. Someone else just collects the ad money and guides the business stuff. You’ll never notice the sound of anything different, except I get to be involved more. So much of my job has become running a business and not making a podcast. I desperately needed that to change.

I chose Stitcher as my new partner because I already knew, trusted, and respected everyone there. The ball got rolling when I called Colin Anderson. He’s the VP of Comedy at Airwolf — they’re part of Stitcher. I literally signed his paperwork a decade ago for him to work in this country. He was on furlough from the comedy production group at BBC Radio, and I signed the paperwork for him to work at KALW in San Francisco. And then he hooked me up with Natalie Mooallem, the VP of Business Development. And she and I hit it off right away because she also happens to be the sister of Jon Mooallem who wrote and performed the amazing song-story collaborations “Wild Ones” and “Genie Chance,” which are like our best episodes ever. So talking to her was like talking to a cousin. And the person who will be my boss is Peter Clowney. He’s the head of original content at Stitcher and he was my editor fifteen years ago. We worked on pilots for public radio and it’s safe to say that if Peter hadn’t been my editor, then 99% Invisible wouldn’t exist today. Then I met a bunch of the Sirius folks and a lot of them had never heard of the show before. But by the end of our negotiations, they had heartfelt and insightful comments about episodes deep in the back catalog that I barely remembered. I like these folks. And you would like them to, but you’ll never notice them. They just give me comfort.

So what’s going to happen with Radiotopia? I am so proud of the things that PRX CEO Kerri Hoffman and executive producer Julie Shapiro, network director Audrey Mardavich and fundraiser Gina James, and all the rest of the behind-the-scenes crew built with Radiotopia. It became more successful than I ever imagined when we dreamed it up in a cabin in rural Massachusetts several years ago. I raised money and worked side by side with amazing podcasters, each of them retaining ownership and control over their own work. Radiotopia is a groundbreaking network and nonprofit collective, it has never been a company on purpose. And as such, even though I was the co-founder, I never owned any part of it. I think that was so weird to people that no one really understood it. I still believe in the ongoing mission of Radiotopia and the amazing work of PRX in the forefront of public radio, and I hope you continue to support them. I certainly do. And personally donating a million dollars to PRX and Radiotopia so they keep going strong.

Whatever cliche you have in mind about what happens in an acquisition when shows move to other networks, this isn’t like that. A bunch of people from the PRX and Sirius teams worked together with good intentions to transform a show that needed to evolve for the sake of its creator. And I am grateful for that. And I’m grateful to you for listening. 99% Invisible will keep on and grow and the team will have even more opportunities to make more stuff and spin-offs with the full support of Stitcher and SiriusXM. I’m really excited to collaborate in ways I never imagined. So thank you, Beautiful Nerds, for getting us here, and thanks for listening.

We were all extremely busy the past couple of weeks, so right now I’m going to play for you a report which is hosted by Delaney Hall — but nothing should be read into that! I’m still the host. This one just happened to be one of my favorite episodes, probably because it was hosted by Delaney Hall. Here you go.

———

Delaney Hall:

This is 99% Invisible. I’m Delaney Hall, filling in for Roman Mars.

[MUSIC]

Delaney Hall:

In 1997, a curator named Katherine Ott was learning her way around the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. She was new to the job — she specialized in medical science. And there was this one storage room in the building where she worked.

Katherine Ott:

It’s like that classic what you’d think of as a dark, dusty, sort of scary, mildly mysterious storage room in a museum…. There were drug jars, there was parts of mannequin bodies laying around.

Delaney Hall:

But the weirdest thing was —

Katherine Ott:

— there was this wheelchair that had go-cart wheels, it was completely customized. It had a Recaro seat that was used in Porsche cars…. But I kept tripping over it, and finally, I’m like, what the heck is this THING? [laughs]

Delaney Hall:

So Katherine Ott started asking around — where did this wheelchair come from? Why is it in storage? And no one at “the Castle” — which is what the staff calls the main Smithsonian building — could really tell her.

Katherine Ott:

Nobody completely understood who had owned it… It had been left at the door of the Castle with a note pinned to it. Like an orphan in a basket. [laughs] The note said: “This was a chair that belonged to Ed Roberts. We think it should be at the Smithsonian.” [laughs]

Delaney Hall:

Ed Roberts. Ott didn’t recognize the name. Not yet.

Delaney Hall:

If you live in an American city and you don’t personally use a wheelchair, you probably don’t pay much attention to the small slope, at most intersections, between the sidewalk and the street. It’s just a ramp… a cut in the curb.

Cynthia Gorney:

They’re all over the country now. Just about any place you find sidewalks.

Delaney Hall:

That’s reporter Cynthia Gorney.

Cynthia Gorney:

But sixty years ago — when Ed Roberts, the owner of that wheelchair, was young — the sidewalks at most urban intersections ended with a sharp drop-off. That’s enough to stop a person in a wheelchair from reaching the next block without help.

Delaney Hall:

And the story of how the first wide-spread urban curb cuts came to be? It starts with a movement that demanded society see disabled people in a new way.

[MUSIC]

Cynthia Gorney:

Ed Roberts was central to that movement. And so were the hundreds of people who helped drag his wheelchair up Constitution Avenue, right in the middle of Washington DC, so it could end up at the Smithsonian. They insisted it was a piece of American history.

Delaney Hall:

Ed Roberts grew up in Burlingame, near San Francisco. He was the oldest of four boys and he loved to play baseball. But one day, when he was 14 years old, he got really sick with a fever.

Zona Roberts:

Within a few days, he was in the hospital.

Cynthia Gorney:

That’s Zona Roberts. Ed’s mom. She’s ninety-eight now.

Zona Roberts:

And within two days of that, he was rushed to an iron lung because he couldn’t breathe anymore on his own.

Cynthia Gorney:

Ed had polio. It had damaged his respiratory muscles so much that he needed the iron lung to stay alive.

Delaney Hall:

Iron lungs aren’t made anymore, but back in the day, they were these full-body respirators that encased polio survivors in metal up to the neck and pulled air in and out of their lungs.

Cynthia Gorney:

Ed’s polio wrecked a lot more than his breathing. It left him paralyzed below the neck. He could move two fingers on his left hand and that was it. His paralysis was permanent. The doctor who told Ed’s parents their son had survived his high fever did not present this as good news.

Zona Roberts:

He said, “Well, how would you feel if you had to live in an iron lung the rest of YOUR life? I don’t imagine you’ve ever been in one — I’ve been in one and it’s not a very good way to live.”

[MUSIC ENDS]

Cynthia Gorney:

In order to escape the iron lung once in a while, Ed taught himself — on his own– a technique called “frog breathing.” That’s a deep-sea divers’ trick where you gulp oxygen into your lungs, the way a frog does. For polio survivors, whose weakened breathing muscles weren’t strong enough to inhale that needed oxygen, “frog-breathing” meant a person could get out of the iron lung for short stretches of time.

Zona Roberts:

You swallow air. [small gulping noise] Like that. You swallow it and then you can breathe. And they kept telling him to stop it, that it was not good for his body. And of course, he kept doing it, because it kept him alive.

Delaney Hall:

And Ed was determined to stay alive on his own terms. Here he is in a “60 Minutes” interview from 1989.

Ed Roberts (ARCHIVAL TAPE):

There are very few people — even with the most severe disabilities — who can’t take control of their own lives. The problem is that people around us don’t expect us to. Think about your own life. If you had people taking care of you, making all your decisions, what is there to life, really?

[MUSIC]

Cynthia Gorney:

Ed was tenacious, but everything was hard. He needed the iron lung while he was asleep, but the frog breathing let him leave it for a while during the day. So he stayed in school, going to campus once a week. When Ed did leave the house, his family ran the maneuvers. They were helping him navigate a world that wasn’t built for a person in a wheelchair.

Delaney Hall:

Ed’s brothers or his dad would help lift him into his chair, drag the chair out of the house, and then lift the chair over curbs and up and down stairs—or, if Zona were alone, she would wrangle strangers.

Zona Roberts:

I’d have to get somebody to help me get the chair up the stairs. So it would be somebody in the back, and somebody on the frame, and get it up, or sometimes it would just be me.

Cynthia Gorney:

Ed graduated from high school, then from a local community college. But when he wanted to go on to Berkeley, in 1962, the university at first said no. He was just too disabled. And where could he safely live? The iron lung — which he still used every night — wouldn’t fit in a dorm room.

Delaney Hall:

Until finally somebody suggested housing him at the campus hospital. A patient’s room remade into a living space for Ed, and all his equipment.

Interviewer (ARCHIVAL TAPE):

Ed Roberts. Side two, tape one. September 15th.

Delaney Hall:

In a series of oral history interviews, much later, Ed remembered what it was like to start as a Berkeley undergrad.

Interviewer (ARCHIVAL TAPE):

Do you remember the day you moved into college and what it was like?

Ed Roberts (ARCHIVAL TAPE):

I do. It was a combination of excitement and scary.

Delaney Hall:

An attendant would wheel Ed to each class, and then Ed would recruit a classmate to help him take notes.

Ed Roberts (ARCHIVAL TAPE):

I started making an announcement at the beginning of class, and usually find a good-looking young woman…

Cynthia Gorney:

He’d give the woman a piece of carbon paper — she would take notes during the lecture — and then she’d give the carbon copy back to Ed at the end.

Ed Roberts (ARCHIVAL TAPE):

It’s such a simple way to take notes. And of course to meet people and get them involved with you. So there were all these little gimmicks.

Cynthia Gorney:

Ed did so much studying and reading, that the mouth-wand he used to turn the pages of books started pushing his teeth out of shape.

Delaney Hall:

So campus officials saw this experiment was working. Newspapers wrote stories about Ed. His mom still likes making fun of the headlines.

Zona Roberts:

“Helpless Cripple Goes to College.” That’s one we all love. (chuckles)

Cynthia Gorney:

And then a second quadriplegic student moved into Ed’s makeshift hospital dorm—a young man who’d been paralyzed in a diving accident and was initially told he should just get used to life as a shut-in.

Delaney Hall:

Then a few more arrived, both to live in the hospital and to find lodgings off-campus. The word started to spread—something unusual was going on at Berkeley.

Cynthia Gorney:

These students had profound and visible disabilities. The state paid special attendants to heft their wheelchairs up staircases and into lecture halls. You couldn’t miss this new presence on campus.

Delaney Hall:

And don’t forget: this was the 1960s.

Steve Brown:

Ed went to Berkeley the same year that James Meredith, a Black man, went to the University of Mississippi and integrated it…

Cynthia Gorney:

That’s historian Steve Brown. He has a genetic syndrome that among other things makes his bones break easily, so he’s a “sometimes wheelchair user” and a co-founder of the Institute on Disability Culture.

Steve Roberts:

So the sixties were a time of lots of protests, and lots of reform, and lots of change. And you know, there’s this very technical historical term: “It was in the air.” And… it was in the air! [laughs]

Cynthia Gorney:

It was in the air for disabled people, too. That improvised dorm in the campus hospital? Those rooms turned into the headquarters for an exuberant and irreverent group of organizers like Ed and Hale Zukas, an assertive guy with cerebral palsy who communicated with a word board and a pointer strapped to his head. They called themselves the “Rolling Quads.”

Delaney Hall:

And like a few other coalitions of disabled young people around the country, they started using a new kind of language to talk about their needs and rights. The radical idea that people with disabilities had civil rights – the right to education, to jobs, to respect, to real inclusion in public life — this fit right into the revolutionary spirit of the 1960s and early 70s. And the Berkeley disabled students had a… Berkeley reputation.

Judy Heumann:

At that time it was an explosive place.

Cynthia Gorney:

That’s Judy Heumann, who had polio as a kid back in the 1940s and has used a wheelchair since then. She was a young New York disability rights agitator when she moved to Berkeley for graduate school.

Judy Heumann:

It was our responsibility to break down the doors. And we had a lot of fun! Because it was much easier to organize a demonstration in Berkeley than in Manhattan, you know, so we could get 30 to 50 wheelchair riders to come to City Hall. That’s a pretty large number.

Delaney Hall:

Notice she said wheelchair “RIDERS,” with a D. Like bicycle riders. Doesn’t have the same feel as “wheelchair-bound,” right?

Judy Heumann:

And disabled people, people from other parts of the country, were coming to Berkeley to work, to go to school, to be part of a disability vibrant community.

Debby Kaplan:

I was instantly attracted to them and what they were doing.

Cynthia Gorney:

Debby Kaplan broke her neck in a diving accident just after college. When she decided to study law, Berkeley admitted her. And Ed and the Rolling Quads said, right away: Come work with us.

Debby Kaplan:

I mean, to people in the disability community… we hung onto each other because we all had this idea about who we were. And nobody else around us did [chuckles.]… Everybody else was stuck in the standard way of thinking about disability back then.

Cynthia Gorney:

Meaning what?

Debby Kaplan:

Charity. And public welfare. And disability means you can’t DO anything. Meaning, you know, Jerry Lewis Telethon.

[TV THEME MUSIC]

Delaney Hall:

The Jerry Lewis Telethon was the late comedian’s annual marathon fundraiser for muscular dystrophy. He mugged for the camera, and brought in celebrity singers, and spent a lot of time smiling down at cute, well-dressed children in wheelchairs.

Cynthia Gorney:

The rising generation of disability rights activists HATED it.

Debby Kaplan:

We just would just cringe every Memorial Day weekend, knowing that all these people were watching Jerry Lewis squeezing money out of people by dramatically playing up the most horrid stereotypes about disability — that having a disability is a fate worse than death; that we should be pitied; that if we do ANYTHING, we are brave and yet really not real people.

Lawrence Carter-Long:

I knew that the only other time I saw disabled people on TV were during those telethons.

Cynthia Gorney:

This is Lawrence Carter-Long. He’s communications director for the Disability Rights and Education Defense Fund. When Lawrence was five, he was a literal poster child for the United Fund charity — because he was born with cerebral palsy, and he was cute.

Lawrence Carter-Long:

I was on the side of buses. I was in fundraising appeals. And everybody would go, “AAAHH.” And they’d open up the checkbooks. It wasn’t until I got a little bit older when I was in college… and I thought, wait a minute. What’s the subtext of that? The subtext was: “Well, you don’t want to end up like this poor kid, do you? Then give us some money.”

Delaney Hall:

As an adult, Lawrence would go on to study the way disabled people were portrayed in the movies and on television, and generally in the public consciousness.

Lawrence Carter-Long:

What became very clear is that there were certain narratives that got told often. That disability was something that we were to be afraid of. That disabled people were objects of pity. And I remember in 1972, there was a controversy around the Jerry Lewis Telethon, where Jerry Lewis said, ‘The man upstairs goofed.”

Jerry Lewis (JERRY LEWIS TELETHON ARCHIVAL TAPE):

I think the man upstairs goofed. He made a mistake. And I think he put people like myself and all these lovely people at the celebrity phones here to repair that goof.

Lawrence Carter-Long:

It rang that bell in my mind in terms of, is THAT what people think of me? That I’m one of God’s mistakes?

Cynthia Gorney:

Back at Berkeley, the Rolling Quads, and Ed Roberts in particular, were one big antidote to the Jerry Lewis Telethon.

Delaney Hall:

Ed flirted with women. He got arrested in college for peeing outside a bar. He told dark jokes about Quadriplegia. Like when a doctor told him he was going to be a vegetable, and Ed answered, “Fine, I’ll be an artichoke. Tough and prickly on the outside, with a tender heart.”

Cynthia Gorney:

A testing counselor once pronounced Ed to be “very aggressive.” Ed liked recounting his response: “Well, if you were paralyzed from the neck down, don’t you think aggressiveness would be an asset?”

Lawrence Carter-Long:

The nature of access, of being included, meant that you had to in some ways force yourself upon the world and say, “we’re here! Hey! HEY! HEY!!” Because the tendency – the programming – for the rest of the country–even here in Berkeley at first, was to say, “We don’t want to see THAT. You’re going to make those normal people uncomfortable!”

Cynthia Gorney:

But by the time Ed Roberts was in graduate school at Berkeley, the disabled students were noticeably, unmistakably part of the community. Even more so because some were zipping around in power chairs, which had been invented to help wounded veterans and were starting to be more available to the general public.

Delaney Hall:

Ed got really interested in power chairs when he first watched another quadriplegic try one out. And now he had one of these new portable ventilators that attached to his wheelchair….so even though he still used the iron lung at night, he could stay away from it a lot longer. And… there was a girl.

Ed Roberts [’60 MINUTES’ INTERVIEW]:

I fell in love. Like many people do. We do that as well. And it became ridiculously inconvenient for me to have my attendant pushing me around in my wheelchair with my girlfriend. It was an extra person that I didn’t need to be more intimate.

Cynthia Gorney:

With a power chair, a person like Ed would still need an attendant for some things. Not for locomotion, though. Not… to go on a date.

Ed Roberts [’60 MINUTES’ INTERVIEW]:

I learned how to drive a power wheelchair in one day. I was so motivated. And it changed, in many ways, my perception about my disability and myself. She jumped on my lap and we rode off into the sunset—or the closest motel.

Delaney Hall:

But think about this. For more than a decade you’ve been able to get around because somebody’s behind you pushing your chair, and now you’re under your own power…. you get to leave that wheelchair attendant behind, but you still have to contend with curbs.

Lawrence Carter-Long:

If you’re trying to get across the street [pause for emphasis] and there are no curb cuts, six inches might as well be Mount Everest. Six inches makes all the difference in the WORLD if you can’t get over that curb.

Delaney Hall:

These guys could only roll independently once they could get over the curb drop-offs on the way. And yeah, they could go hunt for a driveway. But that’s dangerous for somebody in a wheelchair — a driveway sends you right out into traffic. The whole point of a marked intersection is that it shows you this is where it’s safe to cross.

Cynthia Gorney:

The power chair riders — actually, ALL the wheelchair riders — needed what we now call “curb cuts,” those slopes at the corners that make it easy to roll between sidewalk and street.

Delaney Hall:

And here’s where it would be great to be able to tell you about the inventor of the curb cut. The clever person who first thought of cutting little ramps so people could roll into intersections instead of having to step off curbs. But… nobody knows who that was. All we know is that they were NOT a standard feature yet at most intersections – not in Berkeley, not anywhere.

Cynthia Gorney:

Back in the 1940s and 50s, there were a few communities across the country where people had tried to make parts of the built environment more accessible. For example, there was a coach in Illinois working with disabled soldiers who badgered reluctant officials at the University of Illinois– like, shame on you, these men and women were injured fighting for us—until finally the school set up a rehab and education program on its most important campus…with wheelchair sports and wood ramps into buildings.

Delaney Hall:

But by the late 1960s and 70s, this new wave of young disabled activists like the Rolling Quads, they weren’t going to wait around for the occasional enlightened college coach…. They demanded. They were insistent. They didn’t wait for permission.

Cynthia Gorney:

You still hear these stories about the Rolling Quads going out on “commando raids” at midnight… guys in wheelchairs, with their attendants, using sledgehammers — or jackhammers!– to bust up curbs, build their own ramps, and force the city into action. But —

Eric Dibner:

The story that there were midnight commandos is a little bit, uh, exaggerated, I think.

Cynthia Gorney:

Exaggerated, he said. That’s Eric Dibner. In the early 1970s, he was a disabled students’ attendant at Berkeley—sort of a Rolling Quads fellow traveler. And yeah, he says, maybe a few of them got impatient, maybe they did go pour a few ramps themselves.

Eric Dibner:

We got a bag or two of concrete— and mixed it up, and took it to the corners that would most ease the route…so that occurred on, I’d say, less than half a dozen corners.

Cynthia Gorney:

Did any of these runs occur at midnight?

Eric Dibner:

Yes, they were all done under the cloak of darkness. It may have been against the law, right? And so you can call them commando raids, or whatever.

Delaney Hall:

Those commando raids never happened on a grand scale. Instead, most of the progress made by the Rolling Quads was a little more bureaucratic. A little more how real change often gets made.

Cynthia Gorney:

One day in 1971, the Rolling Quads show up at the Berkeley City Council…in a posse. Ed Roberts, who by now is a poli-sci grad student. Hale Zukas, the guy with the pointer and word board, who’s learned Russian and is finishing a math degree. And all their friends, disabled and not. When you picture this, remember that Berkeley’s council chambers are not very big.

Loni Hancock:

We really were kind of stunned to see… a WHOLE LOT of people in wheelchairs wheeling into the council meeting and saying that they wanted to have curb cuts on every street corner in Berkeley because they needed to get around, and they wanted to get around by themselves.

Delaney Hall:

That’s Loni Hancock who was a Berkeley City Council member, and then the city’s mayor, before joining the California state legislature.

Loni Hancock:

We were on a stage, as I remember, so we were elevated. And the people in wheelchairs were down below. Looking up at us. And just looking into their faces, and realizing the effort that it took for them to be there–and that they were requesting something that had NEVER BEEN DONE, to our knowledge anywhere on earth…was an overwhelming sensation. But realizing that it was something we could do, and should do — and would do.

Delaney Hall:

So they did. The world’s first widespread curb cuts program.

Cynthia Gorney:

City Council minutes, September 28, 1971…

Loni Hancock:

(clears throat) “…Declaring it to be the policy of the City that streets and sidewalks be designed and constructed to facilitate circulation by handicapped persons within major commercial areas…that curb cuts be made immediately at fifteen specified corners throughout the city…” The motion carried unanimously.

Delaney Hall:

By the mid-1970s, the disability rights movement was growing and spreading. Groups with a Rolling Quads sort of attitude were multiplying around the country and even the world. And one adjective was pretty much key to the new movement over the next two decades: “Independent.”

Cynthia Gorney:

And for everybody in this crusade, the physical fixes list was ambitious – things that had to change, in the built environment, to make real independence possible.

Delaney Hall:

Not just curb cuts. Wheelchair lifts on buses. Ramps alongside staircases. Elevators with reachable buttons in public buildings and accessible bathrooms. Service counters low enough to let a person in a wheelchair be attended to face-to-face respectfully, not peered down at from way on high.

Cynthia Gorney:

So they got to work.

ARCHIVAL NEWS TAPE:

They’re tired, they’re grubby, they’re uncomfortable, but their spirits are soaring!. The sit-in at San Francisco’s HEW headquarters now is in its third day. And 125 disabled and handicapped are pledging they’ll continue to sit in through tomorrow night, if not longer.

Cynthia Gorney:

In 1977, disability rights protesters hit federal office buildings in eleven cities at once. They were pushing the government to act on long-neglected rules protecting the disabled in all facilities taking federal money.

Delaney Hall:

The San Francisco protest turned into a month-long sit-in, with steady news coverage of people in wheelchairs taking care of each other and refusing to leave…

CROWD SINGING:

“I do believe…that we shall overcome…someday…”

ARCHIVAL NEWS TAPE:

“The occupation army in wheelchairs shows no signs of calling it off.”

Cynthia Gorney:

The sit-in worked. And these images of the grownup disability demonstrator, uninterested in pity kept accumulating.

Delaney Hall:

1980 — disabled people in Denver stage a protest demanding curb cuts. They’ve already blocked traffic until city transit officials promised to put wheelchair lifts on all the buses. Now a couple guys in their own wheelchairs lean over, for the photographers, to whack down at concrete curbs. They’re holding sledgehammers.

Cynthia Gorney:

1988 — trustees at Gallaudet, the national university for the deaf, try to appoint a president who—like every other so far—is not deaf. Angry students boycott classes and shut down the campus until their candidate becomes the college’s first deaf president.

Delaney Hall:

And in 1990, when the sweeping Americans with Disabilities Act gets hung up in the House of Representatives, disabled demonstrators in front of the Capitol Building leave their wheelchairs and crawl up the marble steps—to make sure that bill gets through.

Lawrence Carter-Long:

Wherever you turned on the television, that was the image that you saw….that millions of Americans saw… were disabled people crawling up the stairs of the United States Capitol. Not asking. Not begging. Demanding. DEMANDING, to be a part of society. Boldly going where everyone else had gone before.

Cynthia Gorney:

The ADA wasn’t the first federal legislation designed to remove barriers for disabled people. But its reach was unprecedented. It mandated access and accommodation for the disabled in all places open to the public. Businesses. Lodgings. Transportation. Employment.

Delaney Hall:

And it had qualifiers, to be sure. The ADA required only what was “reasonable,” for employers and builders and so on. There was a lot of argument about that word, “reasonable.” But at the bill’s signing ceremony, in 1990, President George H. W. Bush spoke with emotion about the recent fall of the Berlin Wall, which had divided communist East Germany from the west. Note the tool he mentions.

President George H. W. Bush (C-SPAN):

And now I sign legislation which takes a sledgehammer to another wall, one which has (applause)… One which has for too many generations separated Americans with disabilities from the freedom they could glimpse but not grasp. And once again we rejoice as this barrier falls, proclaiming together, we will not accept, we will not excuse, we will not tolerate, discrimination in America. (applause)

[MUSIC]

Cynthia Gorney:

Ed Roberts–the guy U.C. Berkeley officials once thought was too crippled for their university–finished his master’s degree, taught on campus, and co-founded the Center for Independent Living — a disability service organization that became a model for hundreds of others around the world. He also married, fathered a son, divorced, won a MacArthur genius grant, and for nearly a decade ran the whole California state department of rehabilitation services. He was 56, an international name in independence for the disabled, when a heart attack killed him.

Julia Sain:

I was STUNNED.

Cynthia Gorney:

Julia Sain runs Disability Rights and Resources in Charlotte, North Carolina. It’s one of those programs based on the Center for Independent Living model.

Delaney Hall:

And In 1995, Julia was at the annual march and meeting of the National Council for Independent Living in Washington, D.C. Ed had died a few weeks earlier–and a special memorial for him was now on the schedule.

Julia Sain:

We were going to be marching down the main streets to the Capitol. They were going to put Ed’s wheelchair at the front of the march.

Cynthia Gorney:

The marchers followed the empty wheelchair — which was being dragged along by Ed’s attendant — until they reached the Senate office building. And then once inside, speakers got up to honor Ed’s life and legacy.

Julia Sain:

And Senator Tom Harkin from Iowa gave the eulogy. And he said, you know, when Martin Luther King Junior passed, they built statues in honor of him.

Cynthia Gorney:

But Ed Roberts, Harkin said..there was a better way to honor THIS warrior for another kind of civil rights.

Julia Sain:

They’re going to tear down barriers in his name. And every curb cut is a memorial to Ed Roberts.

Cynthia Gorney:

And sometime later, after the marchers had gone home, or back to their hotels….Ed Roberts’ attendant pushed the wheelchair the rest of the way….and left it on the front steps of the Smithsonian.

Katherine Ott:

The chair’s beautiful to me. (small laugh)

Delaney Hall:

That’s Katherine Ott, the curator at the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. She’s the one who found Ed’s wheelchair in the storage room. His chair now remains on permanent display on the Smithsonian’s website.

Katherine Ott:

It’s all banged and dinged and there’s an imprint of him. There’s a big battery cage in the back. It’s all customized. He has a bumper sticker with the Statue of Liberty on it, with the big letters, YES. Exclamation point. (laughing.)

Cynthia Gorney:

But having Ed’s wheelchair at the Smithsonian does not mean everything is now okay–as anybody in the disability community will tell you. Every broken bus wheelchair lift, every “temporarily out of function” subway elevator, every Uber driver who won’t take a wheelchair, every open manhole cover or car blocking the sidewalk…Most of the New York City subway system, which city leaders years ago decided was just too complicated to make fully accessible… The built environment is still littered with barriers.

Delaney Hall:

Curb cuts are common now, but they’re not at every intersection, even in Berkeley. And when it comes to attitudes and prejudice and assumptions about what people with disabilities can do, and achieve, and enjoy–

Lawrence Carter-Long:

We’ve not yet accomplished full inclusion. We have managed to make it easier, by and large, for people to get into the building. But have we done the work that’s going to make it easier for them to get the education? For them not only to have a job, but have a career? Those things don’t yet exist for many people, even in Berkeley.

[MUSIC]

Delaney Hall:

But here’s what hits you when you go into Lawrence’s office. It’s in a building called the Ed Roberts Campus– and there are actually about a dozen OTHER disability rights organizations in that building too. The place sprawls over an entire block in Berkeley —

Cynthia Gorney:

– and EVERY SINGLE THING ABOUT IT is designed for everybody to use. Inside, like a great celebratory piece of art is this huge, orange, spiraling ramp. It’s two stories high. It’s one of the ways to move between the first and second floors, and all around the ramp, the curved walls are lined with giant photos of demonstrations over the years.

Delaney Hall:

So if you’re listening to this while walking, and you happen to reach an intersection that’s got a curb cut… maybe a bumpy one that lets blind people feel by cane where the sidewalk ends and the street begins…you might hold up just for a second.

Lawrence Carter-Long:

The most important thing I think people can realize is that (pause) by noting it, stopping, pausing, paying attention the next time you walk down the street, the next time you try to cross the street (pause for breath) — Say a little thank you, if you will.

Delaney Hall:

Curb cuts haven’t just been useful for wheelchair riders, but also for people pushing strollers and shopping carts, for elderly people who use walkers, for bicyclists. And this phenomenon has be come to be known as “the curb-cut effect.” Roman Mars will be back to talk with reporter Cynthia Gorney about it, right after this.

[BREAK]

Roman Mars:

So let’s just start with that idea. What IS the curb cut effect?

Cynthia Gorney:

The term gets used to describe a fix that is made to help a particular disadvantaged group of people. In this case, for example, putting ramps into sidewalk curbs so that people who roll, because they have to, can get across a street safely at an intersection. But it’s got much wider applications because it turns out that there are a LOT of these fixes you do that end up having helpful ramifications for a huge group of people. The G.I. Bill, for example, after World War II, designed specifically to help veterans, ends up helping an enormous, wide-ranging population in the United States. The home building industry.

Roman Mars:

Totally!

Cynthia Gorney:

Entire suburban communities, etcetera.

Roman Mars:

And so who’s the first person to apply the curb cut metaphor to this idea?

Cynthia Gorney:

Nobody knows who came up with the term, the “curb-cut effect.” At least, let me rephrase that – I don’t know who came up with the term. Somebody out there surely knows. I was not able to find out.

Roman Mars:

Sure.

Cynthia Gorney:

The idea, however, has been around for quite some time and the most interesting example of recent times, that I learned about, came from Steve Brown, the disability historian we heard from earlier. Steve told me that at some point recently, while he was doing a radio program about his work and disability history, he got a phone call from his own parents who said, “Well, Steve, that was all very interesting. You were good on the show, BUT don’t you remember that back in Kalamazoo, Michigan (where you grew up, by the way), we had some curb cuts?” And Steve said, “What??” and it turned out that in the 1940s, in Kalamazoo, a disabled or injured veteran had gotten so fed up watching other disabled vets struggling up and down the curbs in Kalamazoo. Kalamazoo it turns out at that time had extremely high — unusually high — curbs because of river flooding.

Roman Mars:

Huh.

Cynthia Gorney:

And this guy talked the city officials into, just in a very few corners downtown — into cutting ramps into the curbs. They did it. People started using it. And they got so interested in what was happening that they decided to study it somewhat formally and to see what effect it was having. And so, Steve told me, the officials commissioned a report.

Steve Roberts:

So it said the curb ramps not only helped people in wheelchairs, and people who used crutches, but women – and it did say women – pushing strollers. And delivery men with their deliveries, and bicyclists. And then it kind of ended with something like, it was creating freedom of movement for everybody.

Roman Mars:

And it turns out there are lots of examples of this, that were devised for people who had certain disadvantages, but really benefit all of us.

Cynthia Gorney:

Okay, you’re in a really noisy bar, you’re watching the basketball game, you’re following it with the captions?

Roman Mars:

Right..

Cynthia Gorney:

You’re experiencing the “curb-cut effect.” You’re trying to get into a building, your hands are full of packages. You use the special electronic button or the button you can hit with your hip? You’ve just used a thing that was made for somebody who can’t push a door — or in the earlier example, somebody who can’t hear. We run into examples like this all the time without being aware of it. And in fact when I started working on this story, whenever I would say to people “curb cuts” — they would generally say, especially if they were under the age of about 60 and had not been around Berkeley when the stuff I’m talking about was happening–

Roman Mars:

Mm-hmm. (affirmative)

Cynthia Gorney:

They would say, “Oh, you mean those things that are in the sidewalk so you can put your rolly bag, or your stroller? More easily so you can get those off the curb?”

Roman Mars:

[Laughs] They thought it was meant for them.

Cynthia Gorney:

That’s correct.

Roman Mars:

And not for people in a wheelchair.

Cynthia Gorney:

That’s correct.

Roman Mars:

What was the strangest or most surprising curb cut effect that you found in your research?

Cynthia Gorney:

So the football huddle?

Roman Mars:

Uh-huh? [Laughs]

Cynthia Gorney:

Turns out to have been invented at Gallaudet University. The National University of the Deaf. For students who couldn’t hear.

Steve Roberts:

Because Gallaudet in the late 1800s, early 1900s, had a football team…and they had to figure out a way to communicate with each other, so they got in a huddle and were signing to each other. And therefore began the huddle. (laughing)

Cynthia Gorney:

Swear to me that’s a true story!

Steve Roberts:

It’s true. Look it up.

Cynthia Gorney:

So, I looked it up. It is true. They were signing because they were playing other deaf teams and they got into a huddle because they didn’t want the other deaf teams to be able to read their signs.

Roman Mars:

[laughing]

Cynthia Gorney:

So now, of course, every team in the NFL uses the football huddle.

Roman Mars:

That makes so much sense. I mean, I wouldn’t have thought of that because across a field, you could talk openly, if you had hearing teams, and they couldn’t hear you, you’d be fine.

Cynthia Gorney:

Exactly.

Roman Mars:

That’s amazing. So this is connected to a bigger idea that I think a lot of designers, and maybe a lot of other people, know called “universal design.” So how is this all connected?

Cynthia Gorney:

Well, the person who’s generally cited as the father of universal design, although it’s not clear that he actually used that term, was an architect named Ron Mace. Out of North Carolina. He himself was a wheelchair user and he did a lot of very influential writing. The general message being: look, we shouldn’t be thinking about just people in wheelchairs or just people who can’t see or hear when we design. We should be thinking about designs that work for everybody, regardless of their mobility, their ability to see, their age. And among architects who are advocates of universal design, there’s a set of seven principles which are too elaborate to enumerate here, but they’re very straightforward. Like, things should be simple. They should be easy to use. They should be widely accessible. They should use the best available materials, and so the curb cut has turned out to be a classic example of universal design. Because anybody who rolls, uses it.

Roman Mars:

Right. Mostly I think people think of universal design in the physical space with, like, nice gripped handles for people who maybe are arthritic and curb cuts and things — but the next frontier of universal design is in the virtual space. Because the internet is a place where all of us are living for more and more of our lives, more of our time. How is universal design being applied to the virtual world?

Cynthia Gorney:

Yeah, aside from the football huddle being started for the deaf, my second favorite phrase in all of this reporting was “electronic curb cuts.”

Roman Mars:

Wow!

Cynthia Gorney:

-which is the term that people who work in information technology are now using to talk about ways to make that technology accessible, available to people who can’t see, can’t hear, can’t use a mouse in the old days, can’t type on a keyboard. And Debby Kaplan, the person who had originally been involved in the Center for Independent Living, that we met earlier in the program, does this. This is her specialty now. She works on accessibility of technology – information technology, i.e. electronic curb cuts.

Cynthia Gorney:

You know, those of us who fought for accessibility of the built environment… when we realized that the electronic environment was getting built all around and becoming more and more a part of daily life, we realized that we needed to get involved quickly.

Roman Mars:

And how did they get involved?

Cynthia Gorney:

I think that some of the earliest problems that they wanted to address were how do you make computer information available to people who cannot see, who cannot hear, who can’t use a keyboard. So a lot of the work that they produced ends up being a factor in our daily lives.

Roman Mars:

Mm-hmm. (affirmative)

Cynthia Gorney:

Siri and Alexa can recognize your voice because of technology that was originally designed for people who need to be able to address a computer in that way. There is a program that, let the record show I will never use, that allows your email to be read back to you while you’re driving your car — that again comes from the kind of technology developed by people working on electronic curb cuts. What was originally thought of as something just for people in wheelchairs ended up being just taken for granted by everybody and used in ways that weren’t even originally anticipated for the benefit of many many more people than originally thought of. And that’s true for the things that we do to make the electronic environment accessible also.

Roman Mars:

So now that universal design and the “curb-cut effect” is a pretty widely held, uncontroversial opinion of how design should be done well, where are we in the state of design in the built and electronic world?

Cynthia Gorney:

Well, I would sum that up in my own experience of learning about this by describing a little about my time with Debby Kaplan. At the time that we were meeting with each other, Debby lived just outside Washington, D.C., and spending time with Debby Kaplan is like a crash course in the advances and ongoing challenges of disability fixes — at least in the United States. And we are more advanced than most societies in this regard. So Debby’s an attorney, she’s actually an old friend. My husband and I have known her for many years. She has a very interesting job working on electronic curb cuts and information design. She lives in a community that has been designed with universal design principles, accessible to everybody. She has a handy power wheelchair that gets her everywhere she needs to go. We were there in the winter. So you go down in a nice accessible elevator with Debby and you go out in the street and it’s TOUGH. There are curb cuts in Silver Spring but there’s also snow on the sidewalk. There’s people who left their bicycles on the sidewalk. Now here where we are in the Bay Area, there’s people leaving these new scooters all over the place.

Roman Mars:

(laughs)

Cynthia Gorney:

Every time I see a scooter I think of people in wheelchairs, right? There was snow and I turned to Debby at one time and said, “Well, did they make an extra effort to come and clear the snow for people in wheelchairs who can’t just dart around it like people on foot can?” And she looked at me and just burst out laughing. And said, “Are you joking??”

Roman Mars:

(laughs)

Cynthia Gorney:

So we’ve come a very long way and I think anybody who is presently or about to be grappling with disability will understand how long a way we still have to go.

Roman Mars:

Yeah. And it’s not just about universal design principles in the making of things. We have to incorporate that in our behavior and our sense of courtesy towards one another.

Cynthia Gorney:

Precisely.

Roman Mars:

Thank you so much!

Cynthia Gorney:

Thank you!

———

Roman Mars:

99% Invisible was produced this week by Cynthia Gorney, edited and guest hosted by our executive producer Delaney Hall back in 2018. Mix and tech production was by Sharif Youssef. Music by Sean Real. Kurt Kohlstedt is the digital director. The rest of the team includes Christopher Johnson, Lasha Madan, Vivian Le, Joe Rosenberg, Katie Mingle, Emmett FitzGerald, Chris Berube, Sofia Klatzker, and me, Roman Mars.

We are now a part of the Stitcher and SiriusXM podcast family, now headquartered six blocks north in beautiful uptown Oakland, California. You can find the show and join discussions about the show on Facebook. You can tweet at me @romanmars and the show @99piorg. We’re on Instagram and Reddit, too. You can find other shows I love from Stitcher on our website 99pi.org, including “The Sporkful” from Dan Pashman. I’ve known Dan for years and years. And he was the first person to say hi to me on the company Slack so you should listen to “The Sporkful.” If you want to listen to any of the older 99PI episodes or read any of the articles, they’re all still there, at 99pi.org. The new company didn’t get me one of those official audio logos yet, so badoop-badoop-badoo…. Stitcher, Sirius XM…