Can People with Disabilities Use Your Careers Website?

By Allen Smith | SHRM, October 22, 2018

A company’s jobs or careers webpage is often the way potential job candidates first learn about the organization’s mission, opportunities and culture. But if the site is not accessible to people with disabilities because of the way it is designed, then employers may run the risk of alienating a large pool of candidates or being liable for discrimination.

A website is considered accessible when it is AA compliant, which means it meets the standards of the World Wide Web Consortium’s Web Content Accessibility Guidelines (WCAG) 2.0 AA. Although yet not adopted as the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) standard by federal agencies, WCAG 2.0 AA has been applied by most courts as the ADA standard.

When websites are not compliant, people with disabilities who try to use them may encounter several barriers. And increasingly, that leads to lawsuits against the employer.

Company careers websites should be inviting to people of all abilities and any individuals with disabilities who are available for hire, particularly given the current war for talent. The National Federation of the Blind reports that more than 70 percent of approximately 4 million working-age adults with visual impairments are unemployed. Cornell University Disability Statistics gives a lower estimate of the unemployed individuals with significant visual impairments—56.3 percent—but still more than half of the population. The percentage of these millions of unemployed workers who are looking for jobs is uncertain: A former director of Nebraska Services for the Blind estimated that it was 30 percent during the Great Recession. Regardless, as employers increasingly rely on their websites to attract candidates, inaccessible websites may discourage or prevent a sizable number of individuals with visual and other disabilities from applying.

“Companies seeking to attract talent with disabilities know they must proactively make their processes accessible as an important signal to prospective employees that the company is welcoming to employees with disabilities,” said Carol Glazer, president of the National Organization on Disability in New York City. “This is especially important as unemployment is at its lowest in half a century, and the quest for talent is today’s defining business issue.”

Inaccessible websites predominantly affect people with vision or hearing impairments and people who have difficulty using a keyboard or mouse, said William Goren, a lawyer with ADA Consulting in Decatur, Ga. Blinking images on websites can trigger seizures in individuals with epilepsy.

People with cognitive or learning disabilities can be challenged by complex navigation paths, captcha tests—used to determine whether the webpage user is human—and fast webpage timeouts, noted Corinne Weible, deputy project director with the Partnership on Employment & Accessible Technology (PEAT), funded by the Department of Labor’s Office of Disability Employment Policy.

Common Barriers

According to a 2015 national survey by PEAT, 46 percent of job applicants with disabilities rated their last experience applying to a job as “difficult to impossible.” Common problems included:

- Websites couldn’t be navigated using screen readers that convert text to speech. Many people with vision impairments rely on screen readers to navigate websites.

- Websites couldn’t be navigated using a keyboard instead of a mouse. People who use screen readers, screen magnifiers and voice recognition use keyboard commands instead of a mouse to navigate a website.

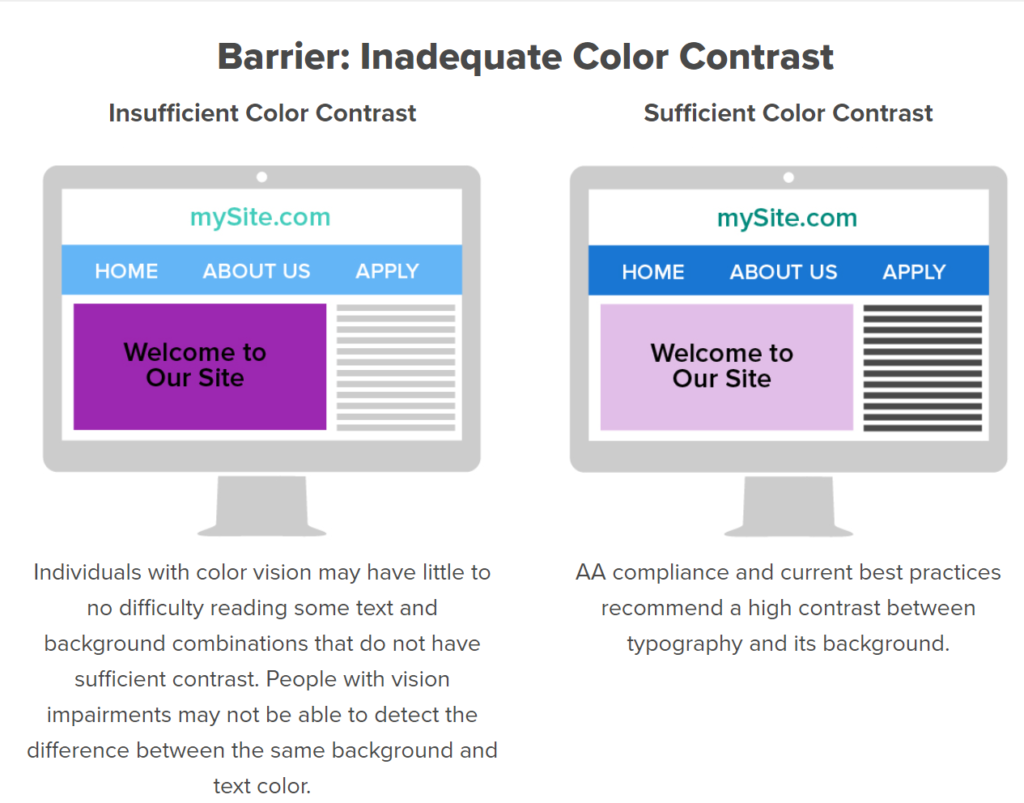

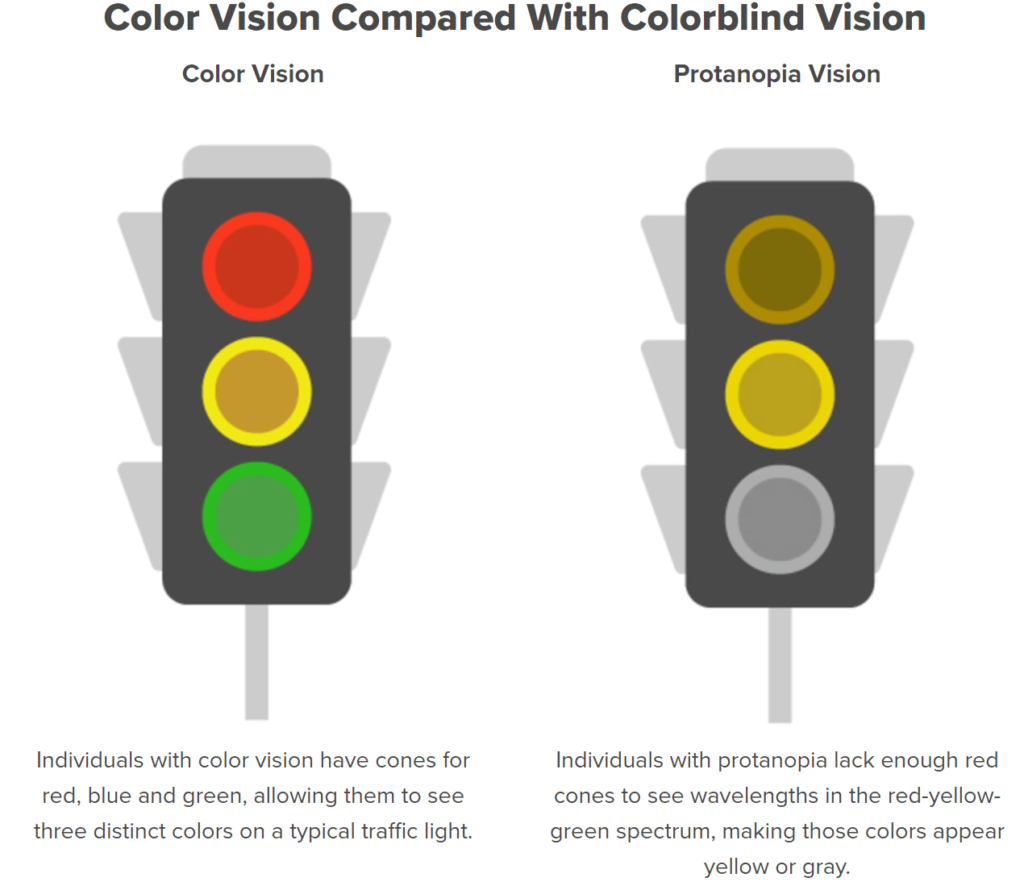

- Applications relied on color, making them inaccessible to people who are colorblind.

- Websites used images that didn’t have alternative text, making the images inaccessible to individuals with vision impairments who use screen readers to navigate websites.

- Videos lacked captions, making the videos inaccessible to people who have hearing impairments.

- Timed assessments in the application process prevented people with cognitive disabilities or learning disabilities from completing applications.

- No contact information was listed for technical support or to request an accommodation, or no one responded to the contact information provided.

“Nearly everyone develops a disability as we age,” Weible said. A 2017 Center for Talent Innovation report found that 30 percent of white-collar employees have disabilities. “Because people all have different and diverse needs, providing a flexible user experience is key,” she stated.

Obstacles for Blind Users

Jonathan Lazar, a professor at Towson University in Towson, Md., has studied the accessibility of job application websites for blind users and co-authored a related article, published in the Journal of Usability Studies. “In that study, our 16 blind participants could only independently submit job applications in 28.1 percent of attempts at 16 companies, due to web accessibility barriers,” he said, noting that the article lists a number of common problems blind users faced in trying to apply online.

These problems included:

- Two buttons, such as “Previous” and “Next,” were visually separate but coded with the same label: “previousnext.” A screen reader would be unable to distinguish what this is.

- A website required users to click on a map to choose the region where they wanted to apply for a job but didn’t have text designations for each region (e.g., “Virginia” or “Va.” in text rather than just a map of Virginia), making it indecipherable to a screen reader.

- Methods for informing blind website users that they had filled out a data field incorrectly were inaccessible (e.g., highlighted the incorrectly filled-out field in red or provided feedback only in a mouseover that could not be accessed by keyboard for those who use screen readers).

- Progress indicators in the application process showed boxes with check marks, rather than providing text that said, “You have completed Step 3 out of X number of steps.”

- Links to job titles all read “Click here” rather than designating the actual job titles as the links, which was confusing to screen readers.

- A red star or something visual indicated a field was required rather than stating “Required field.”

- Automatic timeouts did not give the applicant the chance to indicate that more time was needed.

“The inaccessible online job application will stop you from even applying for the job or require that you contact the company and out yourself as having a disability before you even apply,” Lazar said.

Mike May is executive director of the William L. Hudson BVI Workforce Innovation Center in Wichita, Kan. May used to be blind but had partial vision-restoration surgery and is the subject of the book Crashing Through (Random House, 2007). He is still visually impaired and uses screen readers when visiting websites. The center is a joint partnership between Durham, N.C.-based LCI and Wichita-based Envision, two of the country’s largest employers of individuals who are blind and visually impaired, and was launched to place such individuals in skilled positions and provide accessibility inclusion expertise to U.S. businesses.

May said that his rare vision-restoration surgery revealed basic colors and motion but didn’t help him with reading. He still uses Braille and has a guide dog.

When May encounters inaccessible websites, he said he sometimes contacts online visual assistants—people who are not visually impaired and describe through a live video call what they see through visually impaired people’s smartphones. Aira, a subscription service, provides this assistance, as does Be My Eyes. May noted he can scan websites much quicker with such assistance. But he cautioned that not everyone has access to smartphones or can afford them, and Be My Eyes is staffed with volunteers who are not always available.

Some employers provide a phone number that individuals with disabilities can call if they have trouble filling out online job applications. But often the phone numbers aren’t staffed, said Julie Ann Sowash, senior consultant with Disability Solutions in Bethel, Conn. When people leave messages requesting assistance, the calls are rarely returned, she added.

It should be the applicant’s choice to use such services, May said, instead of having to rely on them because the employer is being “lazy.”

About This Article:

A Life Worth Living has copied the content of this article under fair use in order to preserve as a post in our resource library for preservation in accessible format. Explicit permission pending.

Link to Original Article: https://www.shrm.org/resourcesandtools/legal-and-compliance/employment-law/pages/can-people-with-disabilities-use-your-careers-website.aspx#digitalaccessibility